Chapter 10: Detecting Radiation from Space

Chapter 1

How Science Works

- The Scientific Method

- Evidence

- Measurements

- Units and the Metric System

- Measurement Errors

- Estimation

- Dimensions

- Mass, Length, and Time

- Observations and Uncertainty

- Precision and Significant Figures

- Errors and Statistics

- Scientific Notation

- Ways of Representing Data

- Logic

- Mathematics

- Geometry

- Algebra

- Logarithms

- Testing a Hypothesis

- Case Study of Life on Mars

- Theories

- Systems of Knowledge

- The Culture of Science

- Computer Simulations

- Modern Scientific Research

- The Scope of Astronomy

- Astronomy as a Science

- A Scale Model of Space

- A Scale Model of Time

- Questions

Chapter 2

Early Astronomy

- The Night Sky

- Motions in the Sky

- Navigation

- Constellations and Seasons

- Cause of the Seasons

- The Magnitude System

- Angular Size and Linear Size

- Phases of the Moon

- Eclipses

- Auroras

- Dividing Time

- Solar and Lunar Calendars

- History of Astronomy

- Stonehenge

- Ancient Observatories

- Counting and Measurement

- Astrology

- Greek Astronomy

- Aristotle and Geocentric Cosmology

- Aristarchus and Heliocentric Cosmology

- The Dark Ages

- Arab Astronomy

- Indian Astronomy

- Chinese Astronomy

- Mayan Astronomy

- Questions

Chapter 3

The Copernican Revolution

- Ptolemy and the Geocentric Model

- The Renaissance

- Copernicus and the Heliocentric Model

- Tycho Brahe

- Johannes Kepler

- Elliptical Orbits

- Kepler's Laws

- Galileo Galilei

- The Trial of Galileo

- Isaac Newton

- Newton's Law of Gravity

- The Plurality of Worlds

- The Birth of Modern Science

- Layout of the Solar System

- Scale of the Solar System

- The Idea of Space Exploration

- Orbits

- History of Space Exploration

- Moon Landings

- International Space Station

- Manned versus Robotic Missions

- Commercial Space Flight

- Future of Space Exploration

- Living in Space

- Moon, Mars, and Beyond

- Societies in Space

- Questions

Chapter 4

Matter and Energy in the Universe

- Matter and Energy

- Rutherford and Atomic Structure

- Early Greek Physics

- Dalton and Atoms

- The Periodic Table

- Structure of the Atom

- Energy

- Heat and Temperature

- Potential and Kinetic Energy

- Conservation of Energy

- Velocity of Gas Particles

- States of Matter

- Thermodynamics

- Entropy

- Laws of Thermodynamics

- Heat Transfer

- Thermal Radiation

- Wien's Law

- Radiation from Planets and Stars

- Internal Heat in Planets and Stars

- Periodic Processes

- Random Processes

- Questions

Chapter 5

The Earth-Moon System

- Earth and Moon

- Early Estimates of Earth's Age

- How the Earth Cooled

- Ages Using Radioactivity

- Radioactive Half-Life

- Ages of the Earth and Moon

- Geological Activity

- Internal Structure of the Earth and Moon

- Basic Rock Types

- Layers of the Earth and Moon

- Origin of Water on Earth

- The Evolving Earth

- Plate Tectonics

- Volcanoes

- Geological Processes

- Impact Craters

- The Geological Timescale

- Mass Extinctions

- Evolution and the Cosmic Environment

- Earth's Atmosphere and Oceans

- Weather Circulation

- Environmental Change on Earth

- The Earth-Moon System

- Geological History of the Moon

- Tidal Forces

- Effects of Tidal Forces

- Historical Studies of the Moon

- Lunar Surface

- Ice on the Moon

- Origin of the Moon

- Humans on the Moon

- Questions

Chapter 6

The Terrestrial Planets

- Studying Other Planets

- The Planets

- The Terrestrial Planets

- Mercury

- Mercury's Orbit

- Mercury's Surface

- Venus

- Volcanism on Venus

- Venus and the Greenhouse Effect

- Tectonics on Venus

- Exploring Venus

- Mars in Myth and Legend

- Early Studies of Mars

- Mars Close-Up

- Modern Views of Mars

- Missions to Mars

- Geology of Mars

- Water on Mars

- Polar Caps of Mars

- Climate Change on Mars

- Terraforming Mars

- Life on Mars

- The Moons of Mars

- Martian Meteorites

- Comparative Planetology

- Incidence of Craters

- Counting Craters

- Counting Statistics

- Internal Heat and Geological Activity

- Magnetic Fields of the Terrestrial Planets

- Mountains and Rifts

- Radar Studies of Planetary Surfaces

- Laser Ranging and Altimetry

- Gravity and Atmospheres

- Normal Atmospheric Composition

- The Significance of Oxygen

- Questions

Chapter 7

The Giant Planets and Their Moons

- The Gas Giant Planets

- Atmospheres of the Gas Giant Planets

- Clouds and Weather on Gas Giant Planets

- Internal Structure of the Gas Giant Planets

- Thermal Radiation from Gas Giant Planets

- Life on Gas Giant Planets?

- Why Giant Planets are Giant

- Gas Laws

- Ring Systems of the Giant Planets

- Structure Within Ring Systems

- The Origin of Ring Particles

- The Roche Limit

- Resonance and Harmonics

- Tidal Forces in the Solar System

- Moons of Gas Giant Planets

- Geology of Large Moons

- The Voyager Missions

- Jupiter

- Jupiter's Galilean Moons

- Jupiter's Ganymede

- Jupiter's Europa

- Jupiter's Callisto

- Jupiter's Io

- Volcanoes on Io

- Saturn

- Cassini Mission to Saturn

- Saturn's Titan

- Saturn's Enceladus

- Discovery of Uranus and Neptune

- Uranus

- Uranus' Miranda

- Neptune

- Neptune's Triton

- Pluto

- The Discovery of Pluto

- Pluto as a Dwarf Planet

- Dwarf Planets

- Questions

Chapter 8

Interplanetary Bodies

- Interplanetary Bodies

- Comets

- Early Observations of Comets

- Structure of the Comet Nucleus

- Comet Chemistry

- Oort Cloud and Kuiper Belt

- Kuiper Belt

- Comet Orbits

- Life Story of Comets

- The Largest Kuiper Belt Objects

- Meteors and Meteor Showers

- Gravitational Perturbations

- Asteroids

- Surveys for Earth Crossing Asteroids

- Asteroid Shapes

- Composition of Asteroids

- Introduction to Meteorites

- Origin of Meteorites

- Types of Meteorites

- The Tunguska Event

- The Threat from Space

- Probability and Impacts

- Impact on Jupiter

- Interplanetary Opportunity

- Questions

Chapter 9

Planet Formation and Exoplanets

- Formation of the Solar System

- Early History of the Solar System

- Conservation of Angular Momentum

- Angular Momentum in a Collapsing Cloud

- Helmholtz Contraction

- Safronov and Planet Formation

- Collapse of the Solar Nebula

- Why the Solar System Collapsed

- From Planetesimals to Planets

- Accretion and Solar System Bodies

- Differentiation

- Planetary Magnetic Fields

- The Origin of Satellites

- Solar System Debris and Formation

- Gradual Evolution and a Few Catastrophies

- Chaos and Determinism

- Extrasolar Planets

- Discoveries of Exoplanets

- Doppler Detection of Exoplanets

- Transit Detection of Exoplanets

- The Kepler Mission

- Direct Detection of Exoplanets

- Properties of Exoplanets

- Implications of Exoplanet Surveys

- Future Detection of Exoplanets

- Questions

Chapter 11

Our Sun: The Nearest Star

- The Sun

- The Nearest Star

- Properties of the Sun

- Kelvin and the Sun's Age

- The Sun's Composition

- Energy From Atomic Nuclei

- Mass-Energy Conversion

- Examples of Mass-Energy Conversion

- Energy From Nuclear Fission

- Energy From Nuclear Fusion

- Nuclear Reactions in the Sun

- The Sun's Interior

- Energy Flow in the Sun

- Collisions and Opacity

- Solar Neutrinos

- Solar Oscillations

- The Sun's Atmosphere

- Solar Chromosphere and Corona

- Sunspots

- The Solar Cycle

- The Solar Wind

- Effects of the Sun on the Earth

- Cosmic Energy Sources

- Questions

Chapter 12

Properties of Stars

- Stars

- Star Names

- Star Properties

- The Distance to Stars

- Apparent Brightness

- Absolute Brightness

- Measuring Star Distances

- Stellar Parallax

- Spectra of Stars

- Spectral Classification

- Temperature and Spectral Class

- Stellar Composition

- Stellar Motion

- Stellar Luminosity

- The Size of Stars

- Stefan-Boltzmann Law

- Stellar Mass

- Hydrostatic Equilibrium

- Stellar Classification

- The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram

- Volume and Brightness Selected Samples

- Stars of Different Sizes

- Understanding the Main Sequence

- Stellar Structure

- Stellar Evolution

- Questions

Chapter 13

Star Birth and Death

- Star Birth and Death

- Understanding Star Birth and Death

- Cosmic Abundance of Elements

- Star Formation

- Molecular Clouds

- Young Stars

- T Tauri Stars

- Mass Limits for Stars

- Brown Dwarfs

- Young Star Clusters

- Cauldron of the Elements

- Main Sequence Stars

- Nuclear Reactions in Main Sequence Stars

- Main Sequence Lifetimes

- Evolved Stars

- Cycles of Star Life and Death

- The Creation of Heavy Elements

- Red Giants

- Horizontal Branch and Asymptotic Giant Branch Stars

- Variable Stars

- Magnetic Stars

- Stellar Mass Loss

- White Dwarfs

- Supernovae

- Seeing the Death of a Star

- Supernova 1987A

- Neutron Stars and Pulsars

- Special Theory of Relativity

- General Theory of Relativity

- Black Holes

- Properties of Black Holes

- Questions

Chapter 14

The Milky Way

- The Distribution of Stars in Space

- Stellar Companions

- Binary Star Systems

- Binary and Multiple Stars

- Mass Transfer in Binaries

- Binaries and Stellar Mass

- Nova and Supernova

- Exotic Binary Systems

- Gamma Ray Bursts

- How Multiple Stars Form

- Environments of Stars

- The Interstellar Medium

- Effects of Interstellar Material on Starlight

- Structure of the Interstellar Medium

- Dust Extinction and Reddening

- Groups of Stars

- Open Star Clusters

- Globular Star Clusters

- Distances to Groups of Stars

- Ages of Groups of Stars

- Layout of the Milky Way

- William Herschel

- Isotropy and Anisotropy

- Mapping the Milky Way

- Questions

Chapter 15

Galaxies

- The Milky Way Galaxy

- Mapping the Galaxy Disk

- Spiral Structure in Galaxies

- Mass of the Milky Way

- Dark Matter in the Milky Way

- Galaxy Mass

- The Galactic Center

- Black Hole in the Galactic Center

- Stellar Populations

- Formation of the Milky Way

- Galaxies

- The Shapley-Curtis Debate

- Edwin Hubble

- Distances to Galaxies

- Classifying Galaxies

- Spiral Galaxies

- Elliptical Galaxies

- Lenticular Galaxies

- Dwarf and Irregular Galaxies

- Overview of Galaxy Structures

- The Local Group

- Light Travel Time

- Galaxy Size and Luminosity

- Mass to Light Ratios

- Dark Matter in Galaxies

- Gravity of Many Bodies

- Galaxy Evolution

- Galaxy Interactions

- Galaxy Formation

- Questions

Chapter 16

The Expanding Universe

- Galaxy Redshifts

- The Expanding Universe

- Cosmological Redshifts

- The Hubble Relation

- Relating Redshift and Distance

- Galaxy Distance Indicators

- Size and Age of the Universe

- The Hubble Constant

- Large Scale Structure

- Galaxy Clustering

- Clusters of Galaxies

- Overview of Large Scale Structure

- Dark Matter on the Largest Scales

- The Most Distant Galaxies

- Black Holes in Nearby Galaxies

- Active Galaxies

- Radio Galaxies

- The Discovery of Quasars

- Quasars

- Types of Gravitational Lensing

- Properties of Quasars

- The Quasar Power Source

- Quasars as Probes of the Universe

- Star Formation History of the Universe

- Expansion History of the Universe

- Questions

Chapter 17

Cosmology

- Cosmology

- Early Cosmologies

- Relativity and Cosmology

- The Big Bang Model

- The Cosmological Principle

- Universal Expansion

- Cosmic Nucleosynthesis

- Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation

- Discovery of the Microwave Background Radiation

- Measuring Space Curvature

- Cosmic Evolution

- Evolution of Structure

- Mean Cosmic Density

- Critical Density

- Dark Matter and Dark Energy

- Age of the Universe

- Precision Cosmology

- The Future of the Contents of the Universe

- Fate of the Universe

- Alternatives to the Big Bang Model

- Space-Time

- Particles and Radiation

- The Very Early Universe

- Mass and Energy in the Early Universe

- Matter and Antimatter

- The Forces of Nature

- Fine-Tuning in Cosmology

- The Anthropic Principle in Cosmology

- String Theory and Cosmology

- The Multiverse

- The Limits of Knowledge

- Questions

Chapter 18

Life On Earth

- Nature of Life

- Chemistry of Life

- Molecules of Life

- The Origin of Life on Earth

- Origin of Complex Molecules

- Miller-Urey Experiment

- Pre-RNA World

- RNA World

- From Molecules to Cells

- Metabolism

- Anaerobes

- Extremophiles

- Thermophiles

- Psychrophiles

- Xerophiles

- Halophiles

- Barophiles

- Acidophiles

- Alkaliphiles

- Radiation Resistant Biology

- Importance of Water for Life

- Hydrothermal Systems

- Silicon Versus Carbon

- DNA and Heredity

- Life as Digital Information

- Synthetic Biology

- Life in a Computer

- Natural Selection

- Tree Of Life

- Evolution and Intelligence

- Culture and Technology

- The Gaia Hypothesis

- Life and the Cosmic Environment

Chapter 19

Life in the Universe

- Life in the Universe

- Astrobiology

- Life Beyond Earth

- Sites for Life

- Complex Molecules in Space

- Life in the Solar System

- Lowell and Canals on Mars

- Implications of Life on Mars

- Extreme Environments in the Solar System

- Rare Earth Hypothesis

- Are We Alone?

- Unidentified Flying Objects or UFOs

- The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

- The Drake Equation

- The History of SETI

- Recent SETI Projects

- Recognizing a Message

- The Best Way to Communicate

- The Fermi Question

- The Anthropic Principle

- Where Are They?

Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble Space Telescope has touched every area of astronomy, from the Solar System to the most distant galaxies. In the public eye, it’s so well-known that many people think it’s the only world-class astronomy facility. In fact, it operates in a highly competitive landscape with other space facilities and much larger telescopes on the ground. Although it doesn’t own any field of astronomy, it has made major contributions to all of them. It has contributed to Solar System astronomy and the characterization of exoplanets, it has viewed star birth and death in unprecedented detail, it has paid homage to its namesake with spectacular images of galaxies near and far, and it has cemented important quantities in cosmology, including the size, age, and expansion rate of the universe.

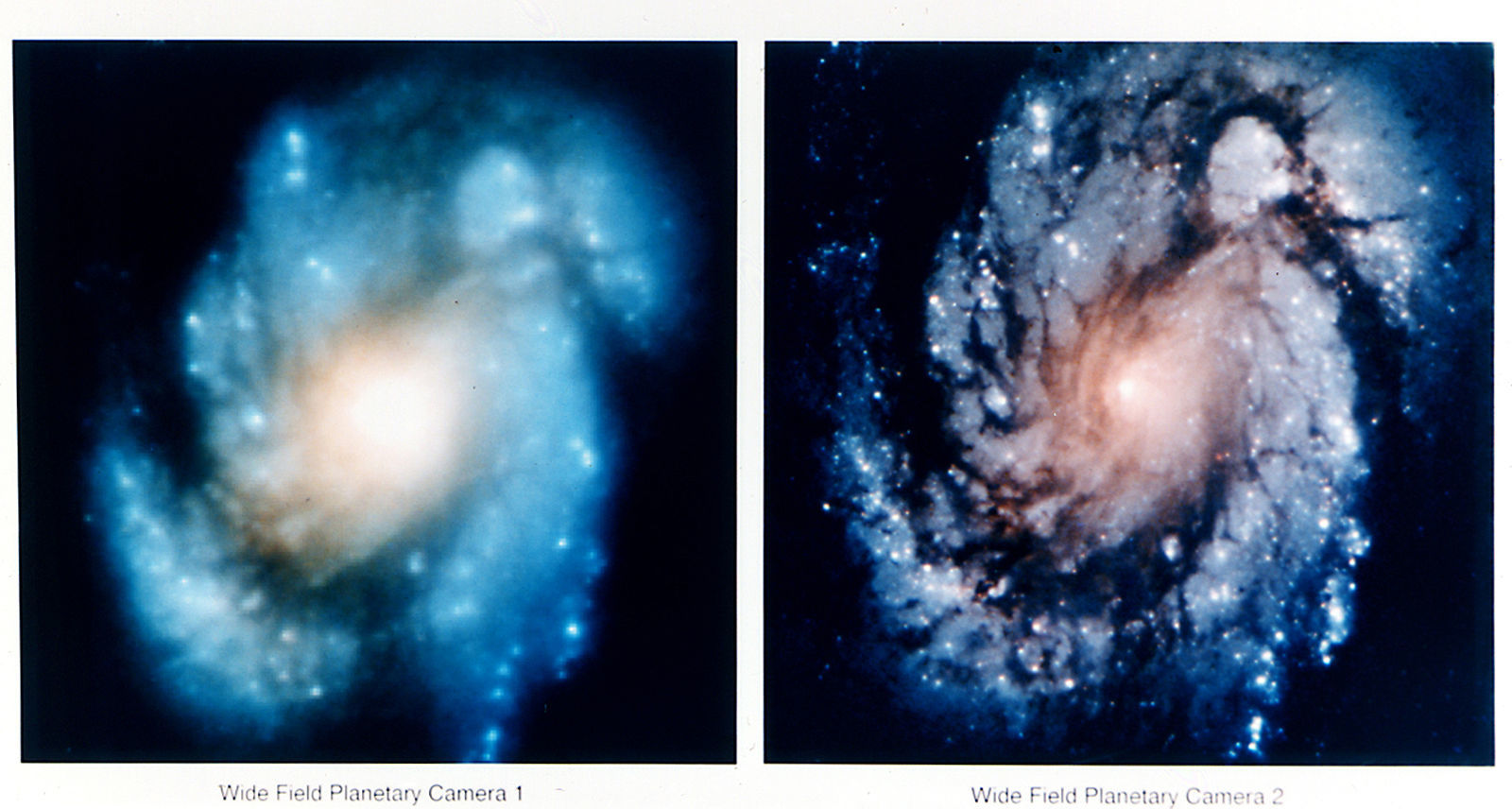

Ranked by size of the mirror, Hubble wouldn’t make it into the top fifty largest optical telescopes. Its pre-eminence is based on three factors associated with its location in Earth orbit. The first is liberation from the blurring and obscuring effects of the Earth’s atmosphere. Ground-based telescopes typically make images far larger than their optics would allow because turbulent motion in the upper atmosphere jumbles the light and smears out the images. Hubble gains in the sharpness of its vision by a factor of ten relative to a similar-sized telescope on the ground. Earth orbit also provides a much darker sky, which affects the contrast and depth of an image. The difference you might see in going from a city center to a rural or mountain setting is only part of the story; natural airglow and light pollution affect even the darkest terrestrial skies. The last feature of a telescope in Earth orbit is its ability to gather wavelengths of radiation that would be partially absorbed or even quenched by the Earth’s atmosphere. Hubble has taken advantage of this by working at invisibly long infrared wavelengths and invisibly short ultraviolet wavelengths.

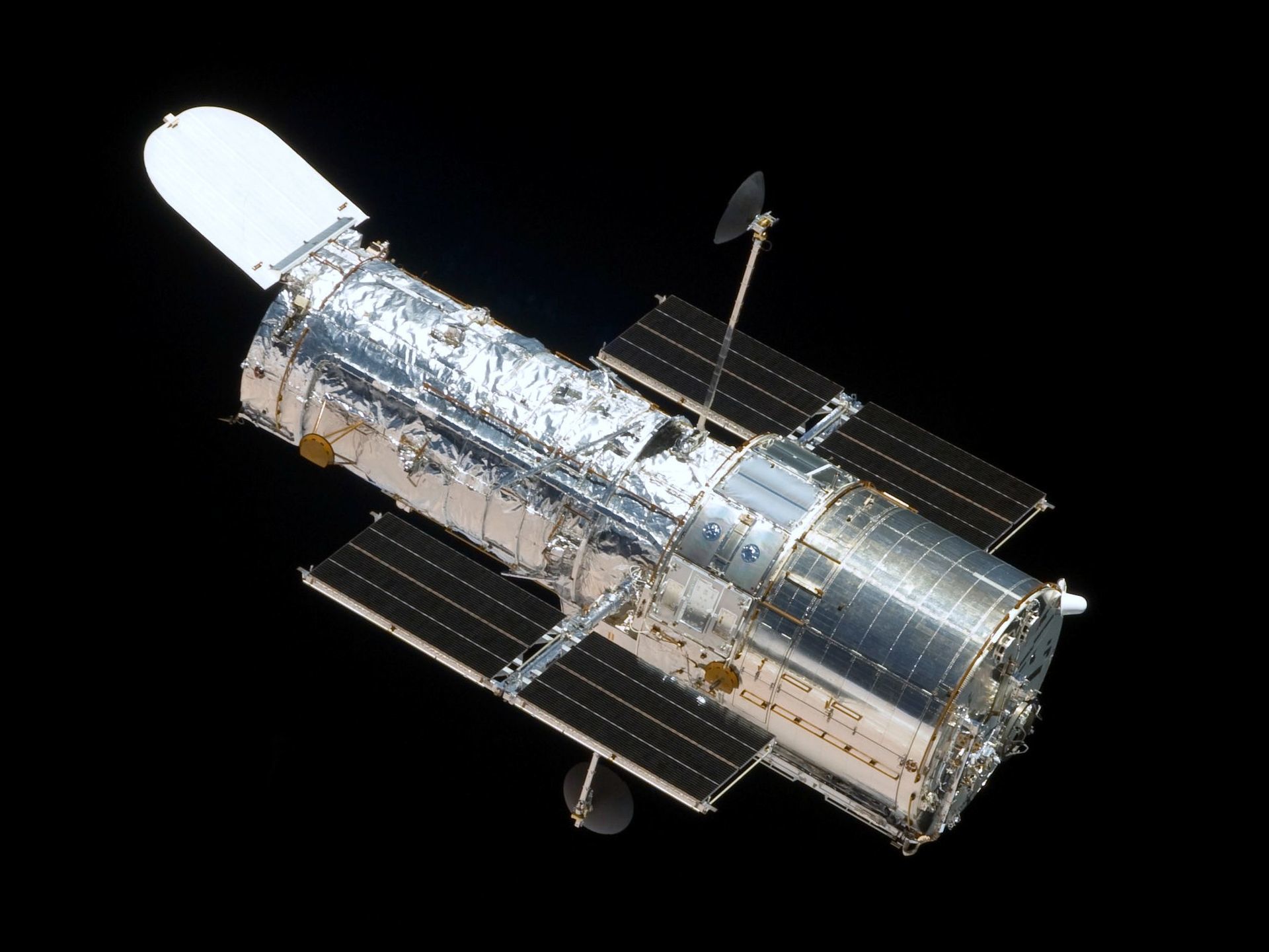

Launched in 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is well into its third decade of operations, and it's easy to take for granted the beautiful images that are released almost weekly. But it was not an effortless journey for NASA’s flagship mission. In 1946, Yale astronomy professor Lyman Spitzer wrote a paper detailing the advantages of an Earth-orbiting telescope for deep observations of the universe. The concept had been floated even earlier, in 1923, by Hermann Oberth, one of the pioneers of modern rocketry. In 1962, Spitzer was appointed chair of a committee to flesh out the scientific motivation for a space observatory. The young space agency NASA was to provide the launch vehicle and support for the mission. NASA had demonstrated the great potential of space astronomy, but also the risks — two of their four missions failed. After the National Academy of Sciences reiterated its support of a telescope in space in 1969, NASA started design studies. But the estimated costs were $400 to $500 million and Congress balked, denying funding in 1975. Astronomers regrouped, NASA enlisted the European Space Agency as a partner, and the telescope shrunk to 2.4 meters. With these changes, and a price tag of $200 million, Congress approved funding in 1977 and the launch was set for 1983. More delays followed. Making the primary mirror was very challenging and the entire optical assembly wasn’t put together until 1984, by which time launch had been pushed back to 1986. The whole project was then thrown into limbo by the tragic loss of the Challenger Space Shuttle in January, 1986. When the shuttle flights finally resumed, there was a logjam of missions so more years slipped by.

Hubble was finally launched on April 24, 1990 by the shuttle Discovery. A few weeks after the systems went live and were checked out, euphoria turned to dismay as scientists examined the first images and saw they were slightly blurred. The telescope could still do science but the original goals were compromised. Instead of being focused into a sharp point, some of the light was smeared into a large and ugly halo. The primary mirror had an incorrect shape. It was too flat near the edges by a tiny amount, about 1/50 of the width of a human hair. Hubble’s mirror was still the most precise mirror ever made, but it was precisely wrong. The spherical aberration problem may be ancient history now, but at the time it was a public relations nightmare for NASA. Its flagship mission could only take blurry images. Commentators and talk show hosts lampooned the telescope and David Letterman presented a Top Ten list of “excuses” for the problem on the Late Night Show.

What went wrong? When the primary mirror was being ground and polished in the lab by Perkin-Elmer, they used a small optical device to test the shape of the mirror. Because two of the elements in this device were mispositioned by 1.3 millimeters, the mirror was made with the wrong shape. This mistake was then compounded. Two additional tests carried out by Perkin-Elmer gave an indication of the problem, but those results were discounted as being flawed! No completely independent test of the primary mirror was required by NASA, and the entire assembled telescope was not tested before launch, because the project was under budget pressure. NASA was embarrassed by the failure. Their official investigation put it succinctly: "Reliance on a single test method was a process which was clearly vulnerable to simple error." As the old English idiom says: penny wise, pound foolish. The propagation of a small problem into a huge one recalls another aphorism from England, where a lost horseshoe stops the transmission of a message and the result affects a critical battle: for the want of a nail, the war was lost.

The problem was fixed in 1993. It helped that the mirror flaw was profound but relatively simple; the challenge was reduced to designing components with exactly the same mistake but in the opposite sense, essentially giving the telescope prescription eyeglasses. Installing the corrective optics was probably the most challenging mission for astronauts since the Apollo Moon landings. Seven astronauts spent thousands of hours training for the mission, learning to use nearly a hundred tools that had never been used in space before. They did a record five back-to-back space walks, each one grueling and dangerous, during which they replaced two instruments, installed new solar arrays and replaced four gyros. The first servicing mission was a stunning success. It also played significantly into the vigorous debate in the astronomy and space science community over the role of humans in space. NASA had always bet that the public would be engaged by the idea of space as a place for us to work and eventually live. But after the success of Apollo, public interest and enthusiasm waned. Most scientists think that it's cheaper and less dangerous to create automated or robotic missions than to service them with astronauts. Hubble was of course designed to be serviced by astronauts, but the problems they were able to solve in orbit, coupled with the positive public response (and high TV ratings during the space walks) persuaded many that the human presence was essential and inspirational.

More servicing missions followed. Each one rejuvenated the facility and kept it at the cutting edge of astronomy research. All of the original instruments have been replaced, along with computers, a power system, and several gyroscopes. The Hubble Space Telescope is reminiscent of the ship of Theseus, a story from antiquity where every plank and piece of wood of a ship is replaced as it plies the seas.

Hubble’s continual rejuvenation is a major part of its scientific impact. The instruments built for the telescope are state-of-the-art, and competition for time on the telescope has consistently been so intense that only one in eight proposals are approved. All this comes with a hefty price tag. Estimating the cost of Hubble is difficult because of how much to assign to the Shuttle launches and astronaut activities, but a 30-year price tag of $10 billion is probably not far from the mark. For reference, the budget was $400 million when construction started and the cost at launch was $2.5 billion. Compared to slightly larger 4-meter telescopes on the ground, Hubble generates 15 times as many scientific citations (one crude measure of impact on a field) but costs 100 times as much to operate and maintain. Regardless of its cost, the facility sets a very high bar on any subsequent space telescope. As Malcolm Longair, Emeritus Professor at the University of Cambridge and former Chairman of the Space Telescope Science Institute Council has observed: "The Hubble Space Telescope has undoubtedly had a greater public impact than any other space astronomy mission ever."